The holiday season has been slow and the weather has not been great, so with this extra time on my hands I have undertaken some deferred shop improvement projects and indulged my curiosities about our neighborhood’s history.

Our building dates back to 1916 when it opened as a hotel. We have yet to discover what type of business originally occupied the storefront but over the years it has been a toy store, an antiques dealer, a pawn shop, and it had been vacant for the last four years until we moved in. (Psst: next door is still for rent. Interested parties have proposed a law office, clothing consignment shop, coffee shop, and waffle shop. That last dream is my favorite.) The hotel upstairs has long given way to single room occupancy apartments — that, or catastrophic fire, seems to be the fate for most of those old hotels.

My project of discovering our corner’s history has involved a few hours (so far) of clicking through the archives of the Minnesota Historical Society. It has been fascinating journey and a highly recommended time-suck.

Top: The view of our corner circa 1936. Source: MN Historical Society

Middle: A present day view of our corner. The parking lot has been replaced by structured parking. Diagonal from us, the Union Gospel Mission daycare has replaced a window glass company and daycare parking replaced the service station. Source: Google Maps

Bottom: Noooooooo! The removal of trolley tracks from our intersection. The Rossmor is visible in the background on the right. The photo is circa 1954. Photographer: St. Paul Dispatch-Pioneer Press. Source: MN Historical Society

Yes, it breaks my heart to see public transportation removed like that, but the deeper I got into this research, the more I realized how lucky we were to avoid the giant eraser of the Interstate Highway and urban renewal. Just a few blocks north, south and west of us, the city was being massively transformed.

Here is how the lead agency — the Housing and Redevelopment Authority — framed the moment and opportunity.

The six years from 1954 through 1960 will be years of great growth and physical change in St. Paul. A large part of the center of the city will be rebuilt through urban redevelopment while a program of related improvements both public and private will take place in all parts of the city.

An integrated development program spurred by private enterprise and public initiative and financed through private, federal, state and local funds is now entering on its most active phase. As part of this program, urban redevelopment projects of the St. Paul Housing and Redevelopment Authority will make available more than 60 acres of choice land near the city center and adjacent to the State Capitol for private, commercial and residential building….

The St. Paul Redevelopment Program consists of two slum clearance projects financed by Federal loans and grants and local grants-in-aid. These projects are located immediately East and West of the Capitol Approach area and on the edge of the Central Business District. (“Redevelopment Rebuilds St. Paul,” Housing and Redevelopment Authority, 1954. Source: MN Historical Society)

Here is how all of that looked with before and after photos.

Top: An aerial view of the Capitol Approach. Rice Street is the major North/South street to the left of the Capitol. Photo is circa 1945. Source: MN Historical Society

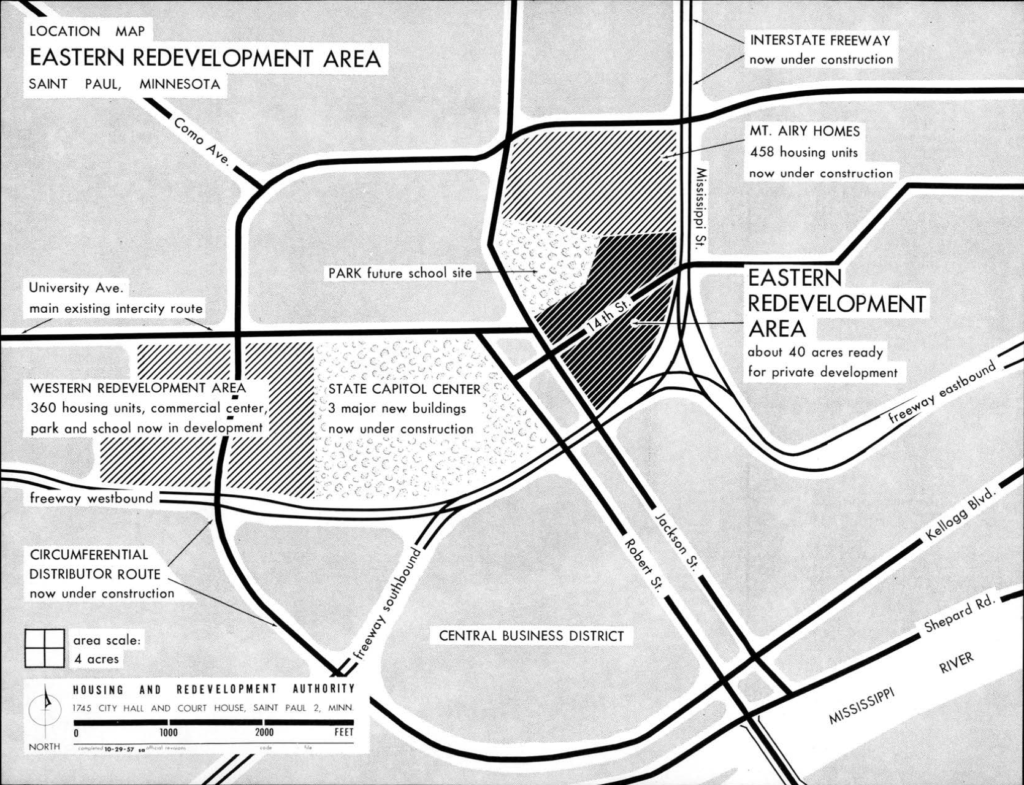

Middle: The Housing and Redevelopment Authority’s proposed development plan for the Capitol campus. Note the areas marked as ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ redevelopment areas. The plan was drafted in 1957. Source: MN Historical Society

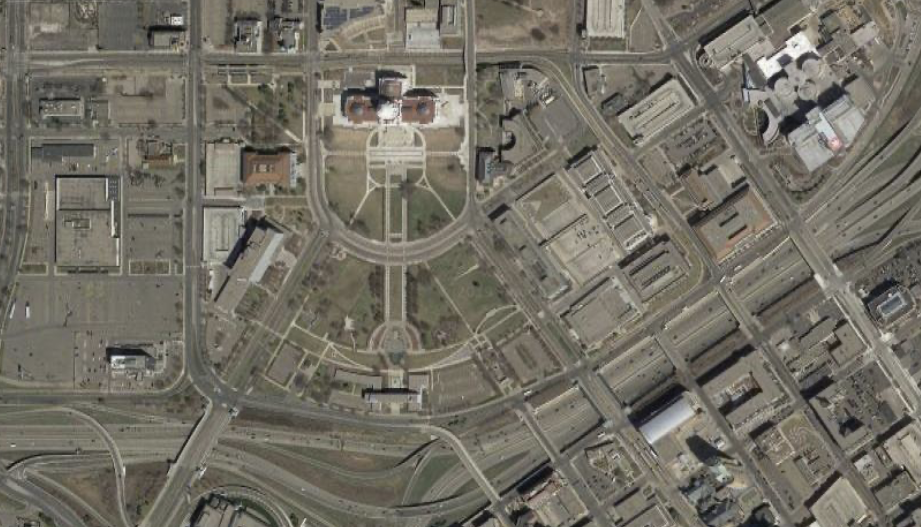

Bottom: The present day view of the Capitol Approach. The Interstate has been built and the designated areas have been redeveloped. The Western zone became a Sears (now closed) and the Eastern zone became the ever-expanding Regions Hospital.

A few hundred families used to live there. With this project and other forced relocations, the neighborhoods often featured substandard housing; unsanitary conditions; proximity to air ground and water pollution; and substandard infrastructure (unpaved roads and flood plains). These justifications for slum clearance are not new or unique to St. Paul; protecting the health, safety and welfare of residents is the charge of government and that responsibility gives it the power to undertake such projects. But… one has to wonder how underinvestment and lax code enforcement might have caused the neighborhoods to deteriorate and, in turn, to justify such a project.

The Housing and Redevelopment Authority’s narrative report on the Redevelopment Plan (1953) suggests that the Western Redevelopment area was a problem in search of a solution.

In addition to the foregoing indication of poor residential conditions, the area presents a serious tax deficit to the community. A study was made of the area bounded by Rice, Fuller, Farrington, and Carroll. It cost $371,800 in city expenditures and county welfare expenditures in 1950, but is repaying only $64,350 on these portions of the 1950 tax rate; thus leaving a deficit of $325,450 for the single year 1950, equivalent to $106 per person residing in the area. For comparison, Ward 7, an old but stable residential area lying west of the St. Paul Cathedral, bounded by Pleasant, St. Clair, Hamline and Carroll, cost $2,586,800 in city expenditures and county welfare expenditures in 1950; it will repay $1,464,700 on these portions of the 1950 tax rate. The resulting tax deficit of $1,122,100 divided by the Ward 7 population comes to $30 per person.

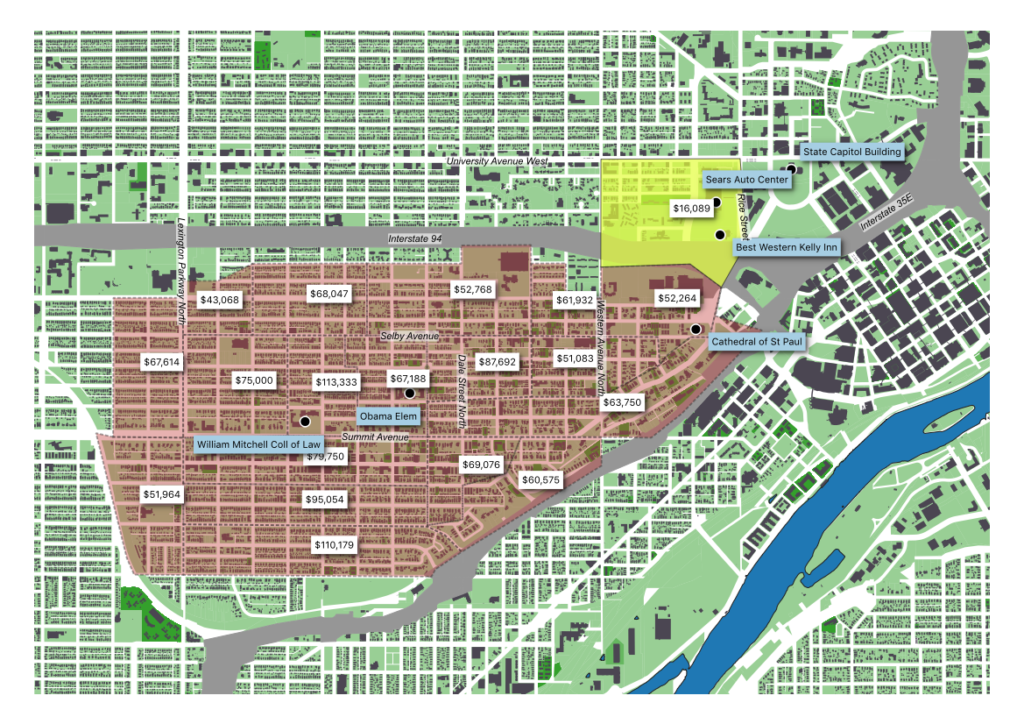

Not exactly a fair comparison in area or demographics. The map below uses Census blocks matched to recently released 2014-2018 ACS 5 year estimates of household income to approximate the redevelopment area (yellow) with the control (red). The 1950 income disparity was greater than 3:1. Now? Click the map below or this link for the most recent estimates

The redevelopment of downtown was not the only urban renewal underway in the 1950s and 1960s. Our family lives on the west side and since moving into the neighborhood we wondered why more development had not happened in the lowlands adjacent to Harriet Island. Actually, it had quite a bit of development once upon a time.

The view from the West Side bluffs looking up Wabasha Street towards the Capitol and downtown. Photo is circa 1948. Source: MN Historical Society

The archives of the Housing and Redevelopment Authority have been very helpful in understanding the redevelopment of St. Paul. The MN Historical Society keeps memos, plans and photographs from the urban renewal era. Reading them fifty and sixty years later is kind of shocking. The following was written in reference to the Upper Levee Renewal Project, which affected an area adjacent to Shepard Road, beneath the High Bridge.

The area selected for urban renewal is about twelve acres in size and lies on the left bank of the Mississippi River, approximately one-half mile from the central business district of St. Paul. This river-front tract of land is known locally as the “Upper Levee.” The urban renewal area, occupied by a rather compact group of about ninety (90) structures, is situated in an industrial environment. This small “island” of housing, faces the Mississippi River, is backed by railroad yards and flanked on either side by heavy industry. Behind it rises the steep river bluffs and high over one end of the settlement, stretches the Smith Avenue bridge. The residents of this area are isolated from other residential areas and cut off from ready access to normal community services and amenities. Churches, schools, parks and shopping facilities are located above, on the bluff, at an inconvenient distance from the young and old residents who reside on the river bank below.

The dwellings in this area are generally old structures, inadequately sited and poorly equipped. The streets upon which they front and back are narrow and mostly unimproved. New public improvements, already approaching the area, will require rights-of-way through the settlement which will drastically reduce it in size. Such a change in the area probably will extinguish whatever social or community value the resident attach to the site as a place to live. Source: MN Historical Society

The neighborhood was known as Little Italy, but note how the report avoids calling the neighborhood by name or even calling it a neighborhood at all. But that last sentence is astonishing: the Authority is acknowledging that by building a 4 lane divided highway through the neighborhood, and demolishing some properties to do so, it will effectively kill it. Remember Mitt’s self-deportation plan from 2012? This is the urban planner’s version: self-eviction and resettlement. All that was written in 1956. More recently, the National Park Service wrote a history of the neighborhood.

This wasn’t the blog post I set out to write. Oh well. Ok, back to working on bikes and the next post which will either be about my favorite repairs of 2019 or the ridership of Nice Ride 2010-2019.

The history of the Smallest Cog’s corner is fascinating. Sadly the worst parts of your neighborhood’s redevelopment has played out in countless neighborhoods throughout the country – sometimes whole populations were displaced or one might say removed in the name of progress. It is amazing the story the maps can tell us. We should always be circumspect when the word redevelopment and improvement appear. Presently the term that we should all be asking questions about is “opportunity zones.” They may be the next great planning disaster. Thanks for all your columns – they are a great read. Happy trails in 2020.